History of Matsudo

The dawn of Matsudo's history

Our Homo sapiens species emarged in Africa about 300,000 years ago and gradually spread around the world. Our ancestors entered the Japanese archipelago about 40,000 years ago. The age in which human beings used tools made of stone is called the Paleolithic period, which continued until the beginning of the Jomon period about 16,000 years ago. The oldest stone tools found in Matsudo are about 35,000 - 32,000 years old, and human history in Matsudo therefore begins in the Paleolithic period.

Ecosystem in the Paleolithic period

The earth goes through repeated cycles of cold glacial periods and warm interglacial periods. We are now in an interglacial period, but the Paleolithic period coincided with a glacial one, and the ecosystem then was consequently different. The Kanto Plain was covered with forests that were a mixture of deciduous broad-leaved trees and coniferous trees. These forests were inhabited by the Naumann elephant (Palaeoloxodon naumanni), Yabe's giant fallow deer (Sinomegaceros yabei), and other large mammals, but they became extinct by about 27,000 years ago, a time that corresponded with the coldest part of the glacial period.

Life in the Paleolithic period

People in the Paleolithic period obtained food by hunting animals and gathering plants. In the ecosystem of the glacial period, there were few usable plants, and animals that could provide food roamed over a wide area. For this reason, continued habitation in a single place held the risk of resource depletion. People therefore led lives that involved residing in tent-like houses and moved frequently to acquire resources at each destination.

Forms of stone tools

Paleolithic archaeological sites yield finds of stone tools and stone fragments. The tools are of various forms to suit the application. They consist of spearheads and other hunting implements, and implements used to dismember and butcher carcasses. Places with large finds of tools and fragments are thought to be sites where tools were made. By piecing together the fragments found there, we can learn about the kind of know-how applied to make tools.

Acquisition of stone materials

The circle of areas that have stone materials suitable for making tools is limited. Such materials cannot be obtained in the Matsudo area. People often used obsidian from Nagano Prefecture and siliceous shale from the Sea of Japan side of the Tohoku region, for example. They presumably acquired these stone materials by finding them as they migrated and through bartering with other groups. At sites in Matsudo, the types of stone materials and their production regions vary with the period. This suggests that there were changes in strategy for acquiring these materials.

Jomon period

The period extending from the initial appearance of pottery in the Japanese archipelago about 16,000 years ago to the start of cultivation of rice in paddies and other farming is known as the Jomon period. In the Kanto region, it is thought to have continued until about 2,400 years ago.

In the Jomon period, pottery was produced in large quantities, but the shapes and designs differ depending on the phases and regions. Research on the period is proceeding while dividing it into six phases based on pottery changes: Incipient, Initial, Early, Middle, Late, and Final.

Ecosystem in the Jomon period

The Incipient Jomon period saw the end of the coldest phase of the glacial period and gradual warming. It was generally colder than it is today, and forests that were a mixture of deciduous broad-leafed trees and conifers spread over the Matsudo area.

With the onset of the Initial Jomon, the interglacial period arrived and gradually brought temperatures that did not differ significantly from those at present. Vegetation exhibited a shift to deciduous broad-leafed trees, whose forests yielded plenty of acorns and other nuts. They became habitats for small and medium-sized animals such as wild boars and deer.

The Jomon Transgression

From around the end of the Initial Jomon into the Early, the climate further warmed, and the surface of the sea rose to a level about four meters higher than at present. The low-lying areas of the Kanto Plain became sea as a result. This phenomenon is termed the "Jomon Transgression", and the bay that intruded into the Kanto Plain, the "Oku-Tokyo Bay". In the Matsudo area, it is estimated that the Nakagawa Lowland in the western part of the city and the valley running through the plateau were the sea.

Adaptation during the Jomon Transgression: Kode Shell Midden

During the Jomon Transgression, tidal flats spread, and there was a transition to an ecological environment that facilitated use of an abundance of marine resources. In adaptation to this environment, many settlements were built along the coastline, and left behind mounds of shells and other discarded items. An excellent example of such a mound is that in Kode, one of the biggest settlements on the coast of Oku-Tokyo Bay. Some of the artifacts unearthed there have been designated as important cultural properties.

Digital Map: Kode Shell Midden

Use of animals

The main targets in hunting in the Jomon period were small and medium-sized animals. Stone arrowheads, which were absent in the Paleolithic period, are unearthed in Jomon sites, indicating that bows and arrows had come into use. People invented tools designed specifically for certain types of prey. Many pit traps have been also found, which were presumably a major means of hunting. Besides the food from their meat, the animals provided vital resources in the form of their furs and bones, which were used to make tools.

Use of plants

Plants were used in various aspects of everyday life. People of course consumed nuts from trees as food, and used tree branches and trunks to make wooden implements and build housing and other structures.

Diverse stone tools were utilized to process plant materials. Typical examples are the use of grinding and pounding stones to crack and crush acorns and the like, and polished stone axes to fell trees.

Use of marine resources

Fish and shellfish were eaten even in the cold Incipient Jomon period and before, but their consumption increased particularly in the initial and succeeding stages. The fishbones and shells discarded in large quantities formed what are called "shell middens", It is thought that this change was due to the rise in sea level because of warming and the appearance of tidal flats suited for fishing and gathering shellfish. In Matsudo as well, many settlements with shell middens have been found, which indicate a high consumption of marine resources.

Housing and settlements in the Jomon period

The ecosystm during the Incipient Jomon basically did not differ from that in the Paleolithic period, and a way of life that was not tied to a single location was consequently the optimal strategy for survival. In contrast, in the environment with a warmer climate beginning with the Initial Jomon, there was no need for frequent movement, because people could count on a supply of resources into the future. In response, they built pit dwellings premised on long-term residence, and formed settlements.

Strange tools

On archaeological sites from the Jomon period strange tools whose purpose is not entirely clear are often found. These may be exemplified by clay figurines with human shapes and stone rod that are thought to be modeled on phalli. They apparently do not have any function useful for getting or processing food. One theory has it that they were used in rituals, and they may afford a glimpse of the spiritual culture in those days.

Interregional networks

In some cases, resources that are only available in a specific area are found in Jomon sites far away from that area. For example, in Matsudo, beads have been found, made of jade from Niigata Prefecture. Also pottery that seem to emulate shapes and patterns that were popular in other regions have been found. The population in Matsudo had evidently constructed network links with other regions for exchange of resources and information.

The birth of agricultual society

The Yayoi period began with the arrival of a wave in rice-farming agricultural culture from the continent. Eventually, the Japanese archipelago entered the Kofun period, when many mound tombs were built, and this made the stage of the state formation in the Kinki region. Historical materials that tell the story of the Yayoi and Kofun periods have been discovered at archaeological sites in Matsudo City.

Rice-farming life

With the arrival of people from the Chinese continent and Korean peninsula, the Yayoi period began, bringing an agricultural culture to the Japanese archipelago. The introduction of rice cultivation drastically changed people's lives. The cultivation and irrigation of rice paddies required groups.This encouraged the emergence of group leaders. In addition, cultivation of rice paddies were owned by the group in question and further tightened the bonds between the land and the people in the community.

Changes in pottery

Studies the pottery allows us to explore the cohesiveness of the time period or region and the movements of the people. During the Yayoi period, the Kanto region was divided into several regional blocs of pottery with different characteristics. However, in the 3rd century, foreign pottery with characteristics of the kinki or Tokai regions began to inflowed into the region. The regional blocs thus disappeared, and the Kanto region entered the Kofun period.

Changes in lifestyle

In the middle of the Kofun period (5th century), there were frequent exchanges with the Korean area, and many people migrated to the Japanese archipelago from the Korean Peninsula. They brought with them new technology and culture, such as the production of unglazed ceramic ware called Sueki, and the use of cooking stoves built into the walls of dwellings. Dietary life also changed greatly with the accompanying appearance of long-bodied pots, large steaming baskets, and other earthenware adapted to cooking on these stoves.

Emergence of kofun

The Kofun period was a time when emphasis was placed on the construction of huge mound tombs called Kofun. Among these, the Keyhole-shaped mound tombs was constructed in many parts of the Japanese archipelago. The source of these burial mound in the Kinki region. The differences in the size and shape of the burial mounds, where funerary rites were shared, reflect the status order, and it is thought that a federation system was formed during the Kofun period, linking the Yamato Kingdoms and local chiefdoms.

Kawarazuka mound tomb No.1

Kawarazuka mound tomb No.1 is built on top of a shell mound dating from the late Jomon period. Because the soil of the shell mound is shellfish mixture with alkali as its main ingredient, the human bones buried in the mound remained in good condition. Excavation revealed that a wooden coffin in the center of the mound buried a mature man over 50 years old. Approximately 172cm tall, and an infant about 3 years old, if they were immediate relatives, they might have been a grandfather and grandson.

Digital Map: Kawarazuka Mound Tomb No.1

Kawarazuka mound tombs group

The oldest known mound tomb in the Matudo City is the Kawarazuka mound tomb No.1, which dates from the mid to late 5th century. Of the five circular mound tombs discovered in this tombs group, Kawarazuka No.1 is the laegest, measuring 26m in diameter and 4m in height. Two burial chambers have been discovered, and excavations have unearthed sword, blades, iron arrowheads, glass beads, and other burial accessories.

Digital Map: Kawarazuka Mound Tomb

Ritual Changes

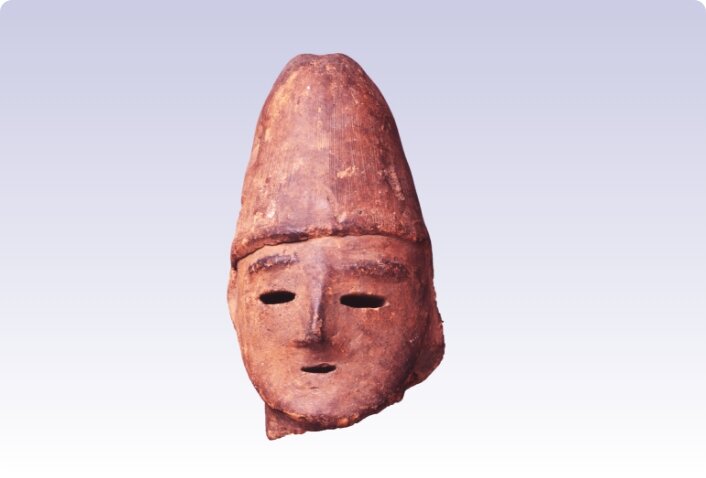

Among the artifacts from the Kofun period, there were imitations made of talc. These were thought to have been used as burial accessories or ritual implements. At first, these artifacts were elaborately made, faithfully imitating the shapes of swords, knives, and farming tools, but these gradually became smaller and cruder. At the same time, it came to be used not only in burial tombs, but also in village rituals.

Burial mound tombs and Haniwa of the 6th century

In the late Kofun period, medium-sized and small circular mounds were constructed in regions where no mound tombs had been built before, and the originality of each region began to emerge. Also, the characteristics of clay figure, known as Haniwa, which erected in the burial tombs, reveal the region of production and extent of distribution. In the Matsudo, there are more Haniwa with characteristics of Saitama and Gunma prefectures than those of the northern part of Chiba Prefecture, indicating the relationship of exchange during the Kofun period.

Beginning of Shimousa Province

From the Nara to Heian periods, a mature State began with the Ritshuryo(low and ordinance) system of ruling as its governing principle. At that time, Matsudo was included in Katsushika Country at the western end of Shimousa Province. Metal belt ornaments (Katai Kanagu) indicating the status of officials and ink-inscribed pottery (Bokusho doki) with characters and pictures drawn with sumi ink on its bottoms and sides have been excavated from the site in Matsudo.

Ancient Japan

The glamorous culture of Heijjo-kyo, the capital of the Nara period, was supported by the Ritsuryo (low and ordinance) System, in which all land and people were administered by the emperor. In 701 AD, the "Taiho Ritsuryo" divided the whole country into administrative units (province, county, and village), each having its own head (Kokushi, Gunji, and Richo).

Ancient Matsudo

The name "Matsudo" is said to have come from "Matsusato no Watari no tu (means ferry crossing at Matsusato)" described in the Sarashina Nikki (The Sarashina Diary). There are not many sites from the Nara to Heian periods in Matsudo City, but the Ono site was a large settlement where many found of pit dwellings and buildings with dug-standing pillars. From this site, ink-inscribed pottery (Bokusho doki) and Metal belt ornaments (Katai Kanagu) indicating the status of officials have been excavated.

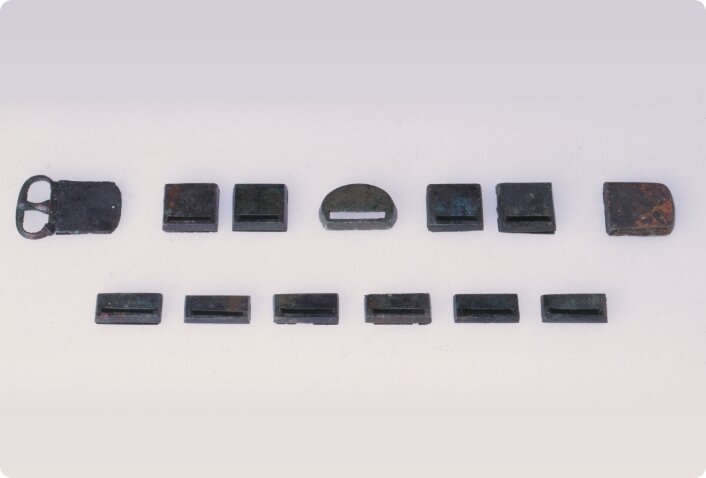

Digital Map: Ono SiteMetal belt ornaments (Katai Kanagu)

At the Ono site, 15 pieces of metal belt ornaments (Katai Kanagu) were found from a pit dwelling. It is very rare for a set of belt ornaments to be excavated from a single site. These belt ornaments indicate the status of officials under the Ritsuryo (low and ordinance) System. Thus, it is thought that the belt ornaments of Ono site was also worn by officials who served the Shimousa Provincial government.

Ink-inscribed pottery (Bokusho doki) : Iwase

At the Ono Site, many ink-inscribed pottery (Bokusho doki) have been excavated. Among them, characters that can be read as "Iwase" are recognized. The area where the ono Site is located was called Iwase Village until 1889. It is possible that the name of this place, Iwase, dates back to ancient times.

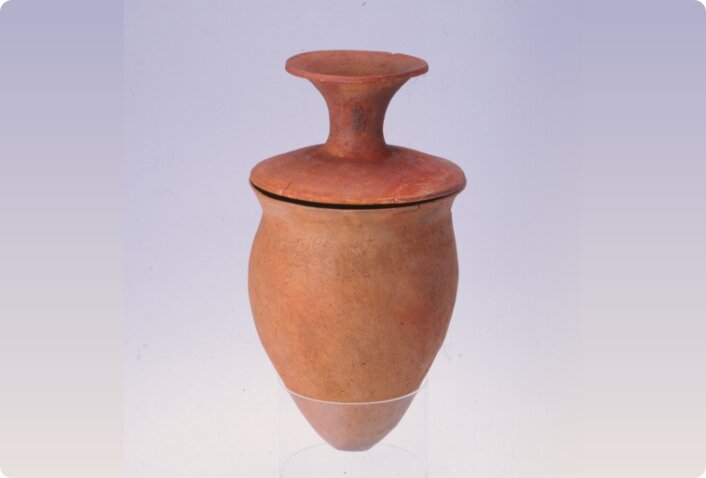

Ink-inscribed pottery (Bokusho doki) : Kuni no Kuriya

At the Sakahana site, a funerary urn containing cremated bone was excavated. the lid is made of a one-legged pottery called "Takatsuki" on the surface of which is inscribed "Kuni no Kuriya" in Sumi ink. "Kuriya" refers to the food and tableware supply facilities of the government. Such pottery is almost always found at ancient government office sites, but this is a very rare example of a funerary urn inscribed with "Kuriya", suggesting that the person buried there was related to the Shimousa provincial gobernment.

Digital Map: Sakahana Site

Overview

There arrived the days when samurai warriors were at the center of Japan's political world. The approximately 500 years consisting mainly of the Kamakura and Muromachi periods around the 12th to the 16th centuries, during which many battles were fought, is called the Middle Ages, and is distinguished from the succeeding early modern age that opened with the country's reunification. In the Medieval zone, the museum's collection provides a look at Matsudo and the world around it during the Warring States period.

The Kamakura and Muromachi Periods

The Chiba clan of the province of Shimousa served Minamoto Yoritomo, founder of the Kamakura shogunate government, and produced many retainers for the Kamakura shogunate government. It long continued to be one of the noted clans in the Kanto region. From the 12th to the 15th centuries, the Kazahaya clan held sway in the Kami-Hongo area, and the Soma clan, in the Takayanagi area. In addition, the Matsudo area and its vicinity were the scenes of activity by members and retainers of the Chiba clan, including the Yagi, Toki, Soya, Ota, Enjoji, Hara and Takagi. This history exerted an influence on the establishment of the Kogane castle and the Kogane domain during the Warring States period (1454-1590 in the Kanto and Tohoku regions).

The Warring States Period

In the Kanto and Tohoku regions, the period of about 150 years from the middle of the 15th century in the Muromachi period to the reunification of Japan under the warlord Toyotomi Hideyoshi toward the end of the 16th century is called the Warring States period. The Kogane domain was an expansive one including virtually all parts of the present-day cities of Matsudo, Ichikawa, Nagareyama, and Kashiwa plus the town of Kamagaya, as well as parts of the town of Abiko and city of Funabashi. The Kogane castle was the headquarters for its control. It was initially built by the Hara clan, who were retainers of the Chiba clan but had more actual power than their masters, and was later transferred to the Takagi clan.

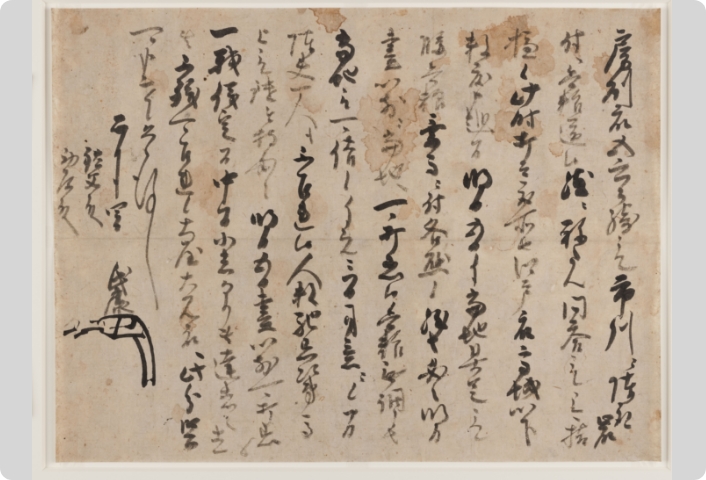

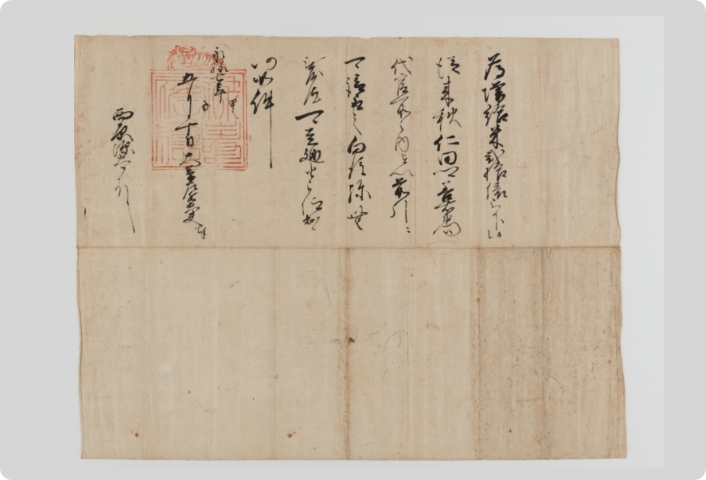

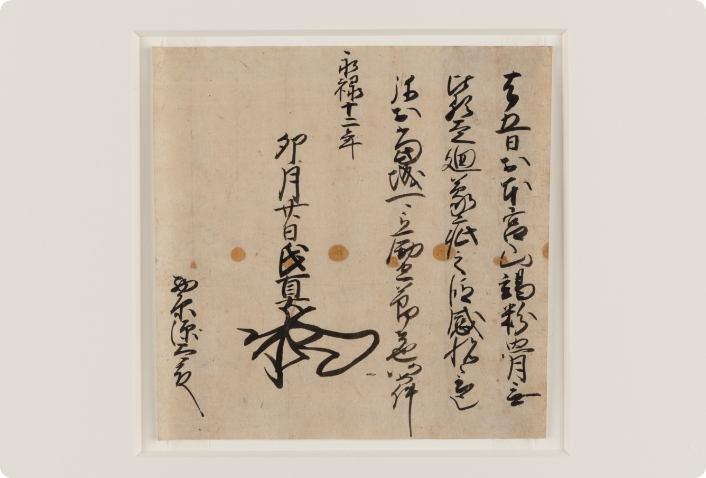

Warring States Period 1:Letter of Hõjõ Ujiyasu

An order for mobilization of troops right before the second Konodai Battle (in the city of Ichikawa).

The battle was a fierce clash between the Satomi clan, who were gaining control over the Boso Peninsula, and the Hojo clan, who had extended their power from the eastern part of present-day Shizuoka Prefecture to the prefectures of Kanagawa, Tokyo, and Saitama. A message was sent by the Takagi clan, lord of the Kogane castle, to Hojo Ujiyasu, to the effect that Satomi forces were having trouble securing provisions in Ichikawa and could not coordinate his troop movements with the Ota clan in Iwaki (in the city of Saitama), and that now was the time to attack. In response, Ujiyasu immediately gave strict orders for the mobilization of all men who could fight, with provisions sufficient for three days, but saw no need for military porters, or logistics. His forces rushed to Konodai and in a flash,winning the battle.

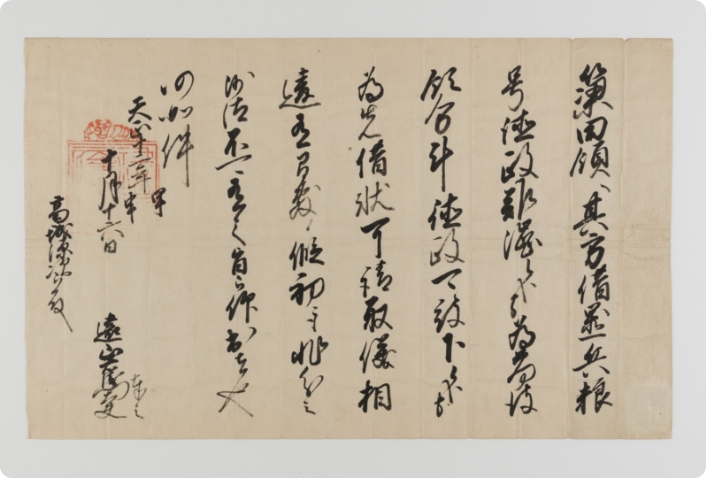

Warring States Period 2: Red seal license by the Hojo Clan

The Satomi were defeated, because they were also unable to coordinate strategy with the Ota and Uesugi Kenshin, whose forces made inroads into the Oda area (at Tsukuba city) from the province of Echigo (Niigata Prefecture). This document was probably received by the Nishihara clan, its addressee (in the Warring States period 1), from the Hojo as a reward for their participation in the battle. The victorious Hojo subsequently made full-fledged inroads to the north and east, even including the province of Shimofusa containing the Matsudo area.

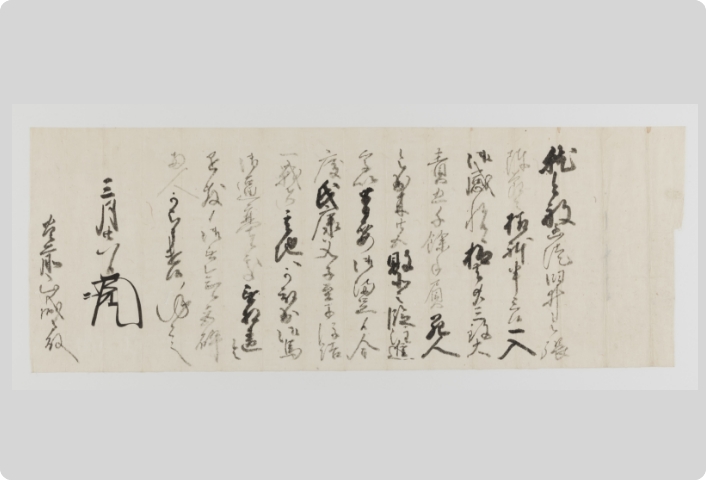

Warring States Period 3:Letter of Ashikaga Yosiuji

In 1566, Uesugi Kenshin attacked Usui Castle (at Sakura City), the main base of the local lord's Hara clan. This letter applauds the Hara clan's success in driving back Uesugi Kenshin's attack. At that time, the Kogane domain, located to the west of Usui, was also in crisis. This is demonstrated from an interdictory notice in the possession of the Hondo-ji temple, a document given by the invading Uesugi forces to the Hondo-ji, which assures the security of the Hondo-ji and the area around it. After his defeat, Uesugi Kenshin hesitated to invade further into the Kanto region, so the Takagi clan's list of enemies became limited to only the Satomi clan.

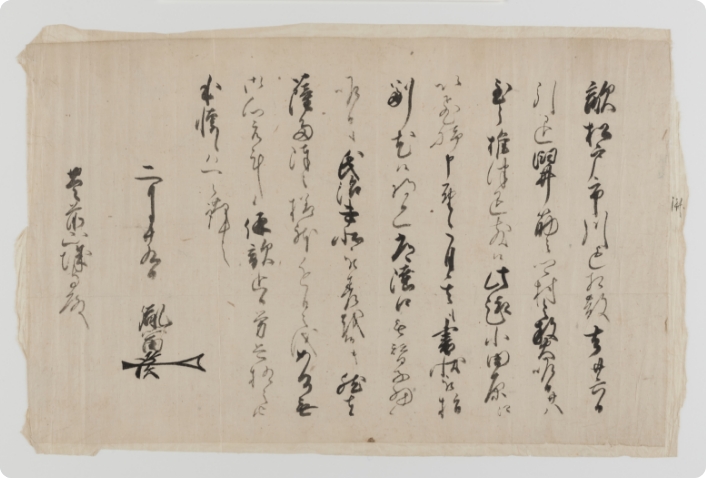

Warring States Period 4:Letter of Chiba Tanetomi

The first line mentions that "the enemy was ravaging lands up to Matsudo and Ichikawa".It meaned that scatters the crops in the Matsudo and Ichikawa areas of Kogane domain, as the fighting continued between the Imagawa and Hojo clans on one side and the Takeda clan on the other in Shizuoka Prefecture.

Meanwhile, in the Warring States period 3, villages are being torched in the Usui area (Sakura City). It is certain that the Satomi, who were employing "energy-saving" tactics that did not directly risk the lives of their warriors, wanted to create a food crisis and refugee problem in the enemy territory while simultaneously dealing with the political situation in the Warring States period 5,6.

Warring States Period 5:Letter of Imagawa Ujizane

The Imagawa clan promised a reward from the Hojo clan for the forces of the Nishihara clan that came to their aid. Although the Imagawa forces fled to the western part of Shizuoka Prefecture in response to the vigorous attack by Takeda Shingen, a counter by the forces of Tokugawa Ieyasu was waiting for them there. At the Hojo order for their redeployment, the Chiba forces at Motosakura Castle (in Shisuimachi) moved to the Kogane castle, and the Takagi forces at that castle, to the base of Edo Castle. As a result, the province of Shimousa fell into a situation of weakened defense that even the Hojo had to acknowledge.

Warring States Period 6:Citation of Imagawa Ujizane

This is a letter of thanks that was sent four months later from the Warring States period 5 to the Nishihara, who was wounded in the protracted fighting. Meanwhile, both the Takeda and Hojo were eager to make peace with Uesugi Kenshin; their apprehensions about an invasion of their domains by his forces in their absence had reached its peak. The Satomi, who were not on the battleground in Shizuoka, were employing "energy-saving" tactics (the Warring States period 4) against the Shimofusa Hara and Takagi clans on the Hojo side, probably in a bid to build up a record of action in the hostilities and thereby strengthen their position after the war.

Warring States Period 7: Comment about letters written by Chiba Tanetomi and Imagawa Ujimasa

An examination of the "Nishihara Documents" and "Buzen Documents" , which are completely different collections of materials in nature, together with other materials, reveals a surprisingly close involvement of battles fought within Shizuoka Prefecture with the Matsudo city area. The connections had a wide scope, from Uesugi Kenshin in Echigo to the north, to the Ashikaga shogun and Oda Nobunaga in Kyoto relied upon by Takeda Shingen to the west. It was in the context of maneuverings in this larger political picture that, in the Kogane domain of the Takagi clan, farmland was ravaged in Matsudo and Ichikawa, and villages were burned down around the Usui Castle of the Hara clan.

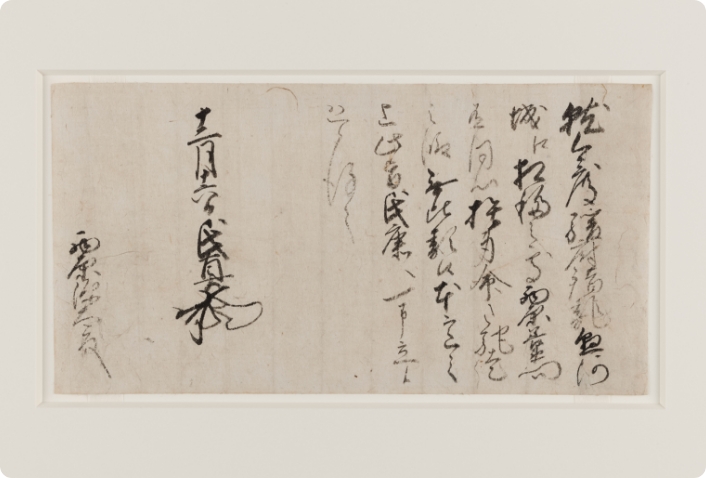

Warring States Period 8: Red seal license by the Hojo Clan

At the time of the Komaki and Nagakute series of battles between Toyotomi Hideyoshi and Tokugawa Ieyasu, forces in the Kanto area entered into a proxy war. More specifically, for a period of four months, the forces of the Hojo allied with Ieyasu battled those of the Satake and Utsunomiya clans on Hideyoshi's side at Numajiri (in the city of Tochigi, Tochigi Prefecture).

It was an emergency situation for the Takagi clan as well, judging from the issuance of an edict aimed at curtailing any disorder in the Kogane domain. The second line of this document offers assurance that the Hojo will not issue a tokuseirei (permitting the cancellation of debt repayment). From this, it can be inferred that the Takagi clan loaned provisions to some party in support of the Hojo forces.

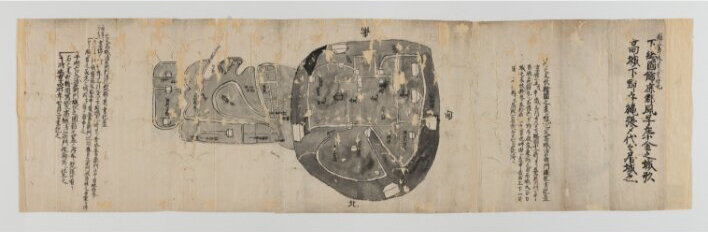

Warring States Period 9: A copy of Illustrated plan of Kogane Castle

This is the oldest drawing of the Kogane castle. Of particular note is the sentence stating that the ruins of a castle whose lord was a Takagi clan karo (chief retainer) in olden times were located in Kurigasawa. Kurigasawa in Matsudo City has a long connection with the Takagi clan; a number of Takagi family branches there can be confirmed to date from as early as the 15th century. This strongly suggests the possibility of the existence to recognize "castle site" in the 18th century. It makes us imagine the Takagi clan's castle before the tradition of the chief retainer's.

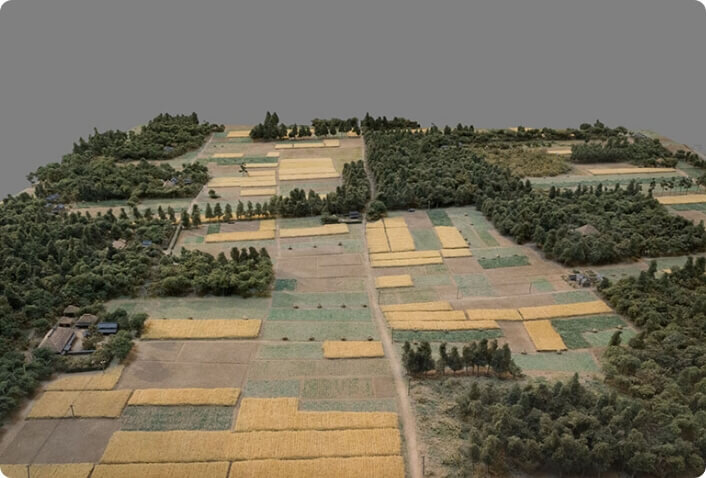

Warring States Period 10: A model of Kogane Castle

This is the central part of the Kogane castle, which dominated the large Kogane domain and had the third-largest area of all castles in the province of Shimousa. The workers dug the valleys cutting into the plateau land deeper and longer. They used the residual earth to make earthworks on the edge of the plateau land, to further increase the difference in elevation and heighten defense capabilities. The parts jutting out on the eastern side of Honjo distrct and Nakajo district defensive enclosures were the foundations of turrets as bases for meeting attacks. Studies in Oyaguchi Historical Park have also found distinctive furrow-form dry moats constructed for defense purposes.

Warring States Period 11: "Kawarake" (an unglazed earthen vessel), copper coins, and bullets

Unglazed earthen vessels are the type of artifact that is most often found in the former sites of castles that functioned as space for everyday life activities. This piece is, properly speaking, a cup for sake, but a lump of copper is stuck to it for some reason. A close look reveals that the lump is a melted copper coin from China. Although bullets were usually made of lead, excavations have also turned up some with copper mixed in. To melt copper requires a high-temperature furnace, and there may have been a shortage of lead for bullets at the Kogane castle.

Villages of Edo period

The Warring States period came to a close when Tokugawa Ieyasu established the Edo shogunate government, which ushered in an age of peace. The shogunate government controlled the country using the village as the basic administrative unit, and ordered three sets of officials (nanushi/ village headsmen, kumigashira assistant headsmen, and hyakushodai peasant representatives) to pay the annual land tax and otherwise run the villages. Most of the 57 villages that were located in what is now the city of Matsudo dated from the Warring States period, but 13 were "new villages" created in the early Edo period by the transformation of low-lying land along the Edogawa River into rice paddies and the subsequent development of farm fields in the plateau zone.

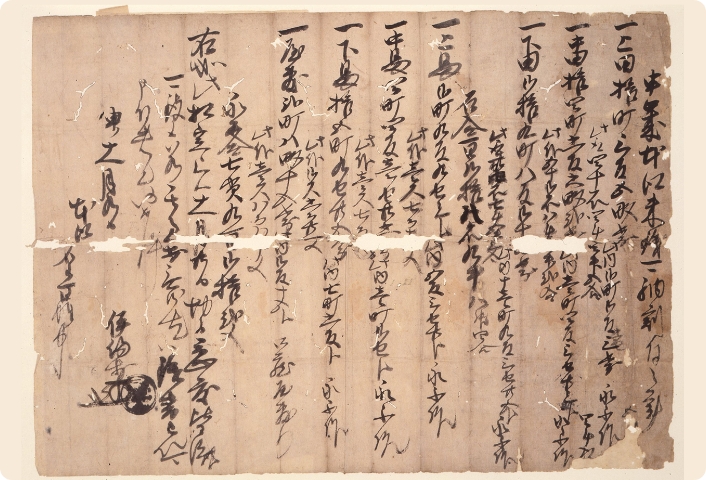

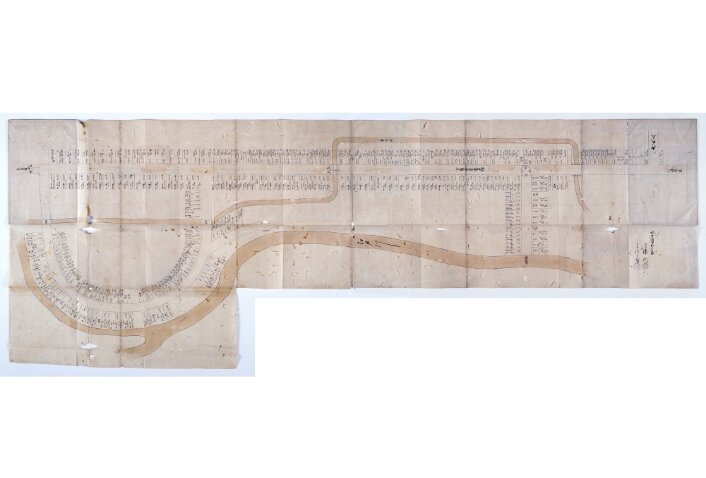

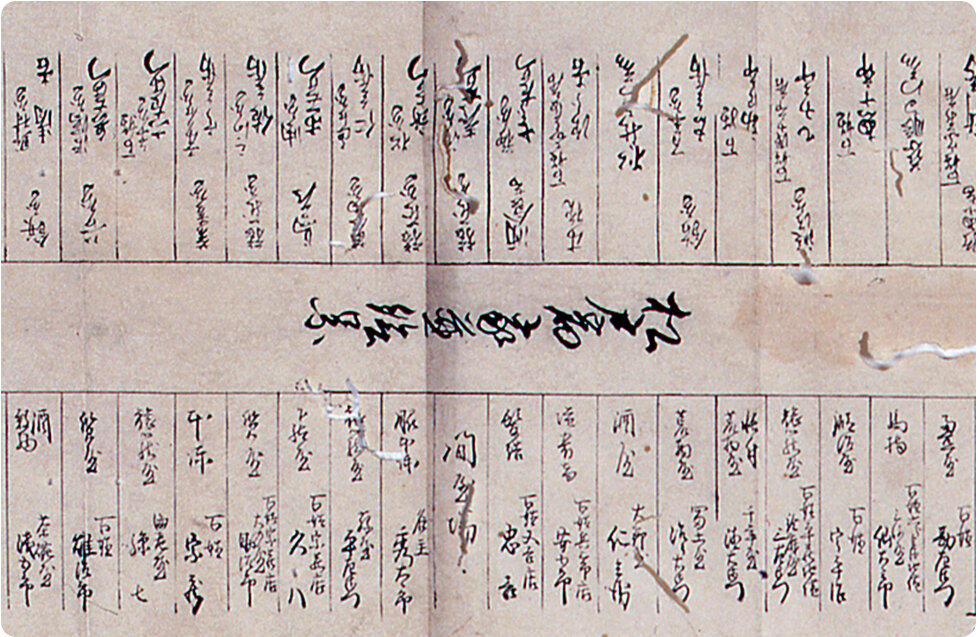

Land surveys and village tax burden

To collect the yearly land tax, the domain lord surveyed the area of all farmland and housing lots, examined the quality of paddies and farm fields, and determined the people farming them. The data from this survey were recorded in the land survey ledger, a copy of which was left in the village. The survey findings provided the basis for determination of the village tax burden, through conversion of the village's production capacity into a quantity of rice, which was the standard for taxation.

The scheme of the yearly tax payment

In autumn, the domain lord fixed the amount of tax to be paid based on a survey of the rice harvest in each village. He entered the survey results on a document showing the tax allocations, and ordered payment. The officials in each village collected the tax from the peasants and paid it to the lord.

Village entertainment - koshinko vigils

There was a belief that three worms called sanshi lived in the human body, and that they would escape from it while the host was asleep on the day of koshin (the 57th day in the 60-day Chinese zodiac cycle) and ascend to heaven, in order to tell the deities of the host's misdeeds and have his or her life shortened. In response, there arose the custom of koshinmachi vigils, i.e., staying up all night on that day so that the worms could not slip out of the body. In the Edo period (1603 - 1868), this custom was widely practiced; koshinko (koshinmahi vigils association) were held throughout the country. Only men were permitted to participate in them, and enjoyed Buddhist-style vegetarian food and sake at them all night long. In Matsudo, there remain over 300 koshinko monuments commemorating the organization of these gatherings.

Food at koshinko vigils

This register for the koshinko vigil held at the village of Kamishiki in 1805 contains entries for the foodstuffs purchased and the prices of kitchen utensils. Based on these data, we reproduced boiled rice, mashed tofu salad, boiled vegetables, clear soup, and sake.

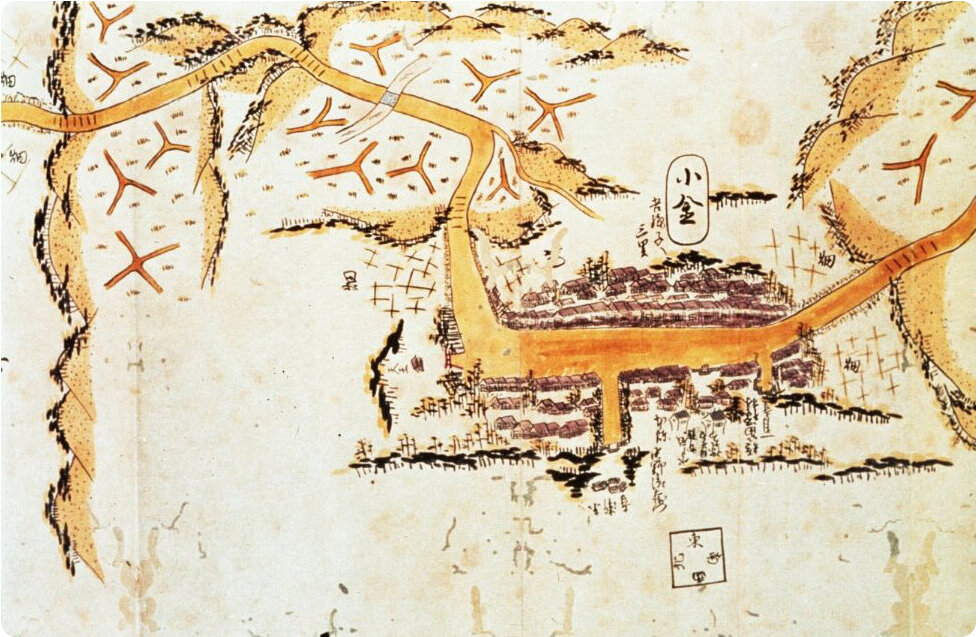

Highway stations and river markets

Matsudoshuku and Koganeshuku were stations on the Mito Highway. The two stations each had official main inns (honjin) and subsidiary inns (waki-honjin) where samurai worriers stayed, and toiyaba administrative offices that dispatched men and horses for transporting freight. The transport proceeded in a relay system that required freight to be unloaded and loaded again at each station. The station towns were hubs of transport, and their bustling streets had many inns and stores. On the banks of the Edogawa River near the Matsudoshuku station was a river port with a market where goods were exchanged.

Journeying on the Mito Highway

The Mitodochu Highway (officially termed the "Mito-Sakura Highway") started in Nihonbashi (now in Tokyo's Chuo Ward). It branched off from the Nikkodochu Highway at the Senju station (in Adachi Ward), and divided into the Mitomichi and Sakuramichi Highways at the Niijuku ( Katsushika Ward), which was the next station. Matsudoshuku was the second station on the highway and Koganeshuku, the third. The Mitodochu Highway went through 16 stations before ending near Mito Castle, and had a total length of about 120 kilometers. It was closely connected with the Mito branch of the Tokugawa clan, as suggested by the establishment of a honjin especially for its members at the Kogane station.

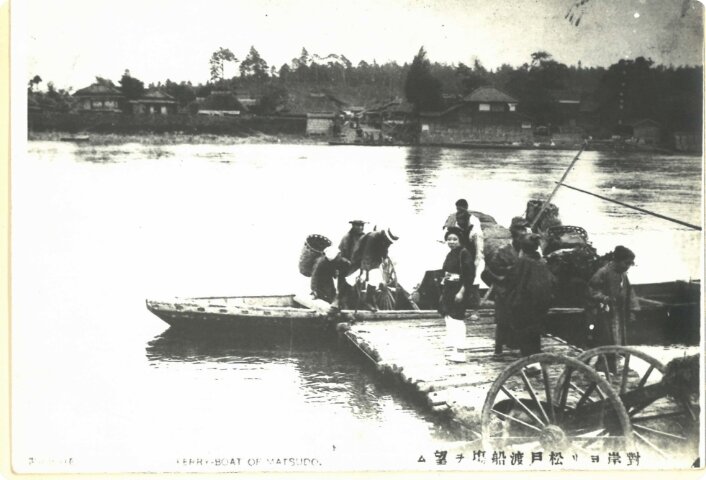

Kanamachi-Matsudo checkpoint

In 1616, the Edo shogunate government designated Matsudo as the site of one of the only 16 barriers for checking boats in the Kanto region. The Kanamachi-Matsudo checkpoint was built on the other side of the Edogawa River, in the village of Kanamachi (Katsushika Ward), and officials there checked the passengers and cargo of boats. The shogunate government's prime objective in setting up these checkpoints was to prevent the unauthorized influx of guns and other weapons into Edo, and the exit of high-born women from it without permission. Travel by commoners required a permit also proving identity.

Matsudoshuku station

As traffic increased on the Mitodochu Highway, Matsudoshuku further expanded, and the number of districts in the town increased to seven: Shimoyokocho, Miyamaecho, 1 Chome, 2 Chome, 3 Chome, Nayakashi, and Hiragata. At its center, however, was Miyamaecho, which contained the honjin, waki-honjin, and toiyaba. Along the highway in Matsudoshuku station were 317 buildings, including 28 inns and 33 eating places.

Kogane station

Kogane was an important node of transportation from ancient times and encompassed several residential districts by the beginning of the Muromachi period. The Edo period brought the development of the districts of Kamimachi, Nakamachi, Shimomachi, and Yokomachi. Shimomachi contained Ichigetsuji, a temple for Komuso monks. Nakamachi was the site of the honjin, waki-honjin, and toiyaba as well as the Tozenji temple, a school run by the Jodoshu sect of Buddhism. Kamimachi included the official residence of the Watanuki clan, the holder of the post of the noma (wild horse) magistrates managing the Kogane pasture land. Yasaka Shrine was located at the fork of the road leading to Yokomachi.

Station towns and sukego

For the transportation of travelers on official business and their freight, the shogunate government obliged residents of the station town to provide horses and manpower. The Matsudoshuku station had to be prepared with 25 laborers and 25 horses, and the Koganeshuku station, eight laborers and eight horses. When traffic increased, however, this was no longer enough, and the shogunate government imposed the sukego-yaku, a duty obliging villages in the surrounding area to provide the necessary extra laborers and horses. These obligations placed a heavy burden on both the stations and the villages.

Matsudo market

A riverside market was established in Matsudo, which was also a port on the Edogawa River, one of the main distribution arteries in the Edo area along with the Tonegawa and Arakawa rivers. This market sent a large quantity of people and goods both in the direction of Edo and to upstream areas. For example, fish freshly caught off the coast of Choshi were taken by boat up the Tone River to Fusa (Abiko), where they were unloaded for transport by horse to the Matsudo market, and then transported by boat to the fish market in Nihonbashi (Chuo Ward), from which they found their way onto the dinner tables of the people of Edo.

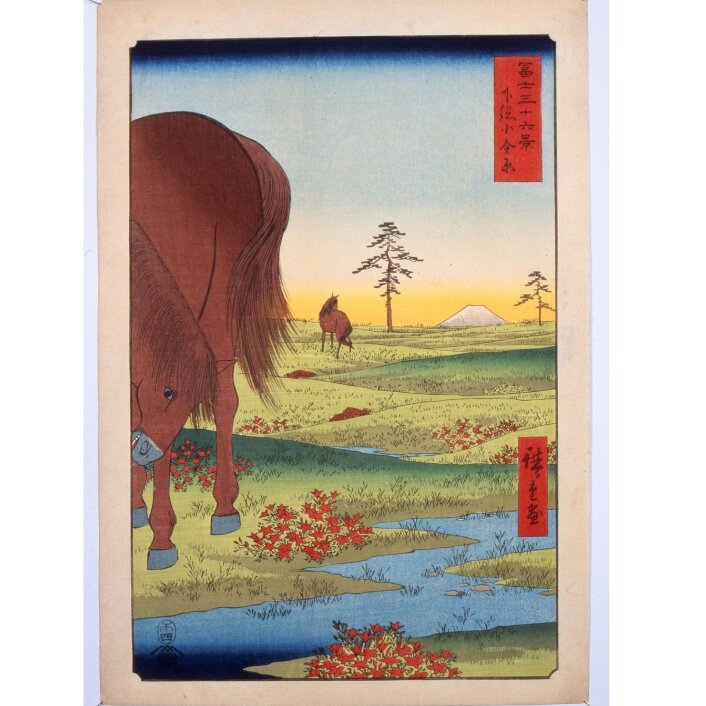

Scale models of Matsudokashi riverbankKogane pasture land and shogunal oshishigari boar hunts

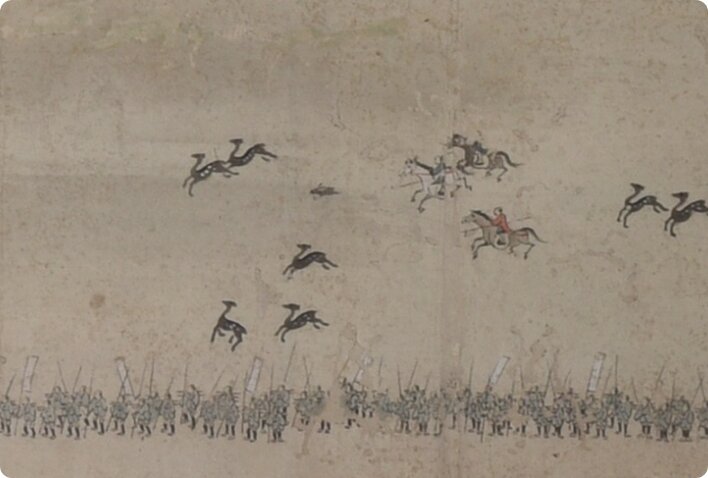

The Edo shogunate government established pasture land for horses in Koganemaki and Sakuramaki in the plateau zone of Shimousa. Once a year, roundups were held to capture wild horses of good quality. The stallions were used as mounts for samurai worriers, and the mares, for farm work and transportation. The Edo shoguns led a total of four deer hunting expeditions in the environs of the present-day Matsudo districts of Goko and Matsuhidai. Large numbers of samurai worriers and peasants were mobilized to assist the hunting. This was called the shougnal oshishigari deer hunt at Koganehara.

Kogane pasture land

The Koganemaki pasture land established by the shogunate government during the Keicho era (1596 - 1614) originally consisted of seven ranches, but this was later reduced to five: Takadadaimaki, Uenomaki, Nakanomaki, Shimonomaki, and Inzaimaki. The pasture land had an enormous scope extending from the city of Noda in the north to the northern part of the city of Chiba in the south. The Matsudo area contained the Nakanomaki ranch.

Ema depicting the wild horse roundup

Generation after generation, the Koganemaki pasture land was managed by the Watanuki family, who were the hereditary noma magistrates residing in the town of Kogane. Members of the leading farming families in the vicinity cared for the horses and maintained the pasture as ranch hands. The Koya Kannon temple has an ema (votive tablet with a picture of a horse) that was dedicated in 1882 by members of these families who had lost their employment on ranches and felt a fondness for the old days. The ema has pictures of horses being rounded up, spectators enjoying the sight, and even outdoor stalls set up to cater to them.

Digital Map: Nomayokedote embankment and the Fukushoji Temple

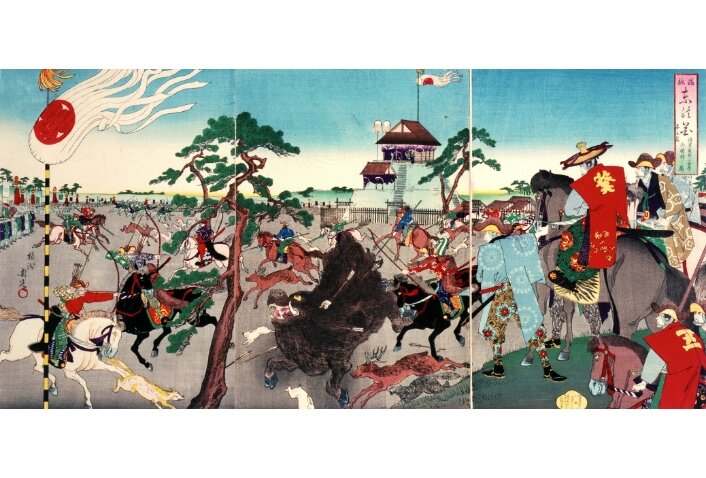

Shogunal oshishigari boar hunts

The Tokugawa shoguns held large-scale hunts that were termed "Shogunal oshishigari deer Hunts". More specifically, there were a total of four such hunts over the years 1725 to 1849, led by the three shoguns Yoshimune, Ienari, and Ieyoshi. The purpose was to reduce the population of deer, boars, and other animals that menaced crops, and conduct military training. Large numbers of shogun retainers, lower-ranking retainers, and farmers (to work as beaters) were mobilized to assist the hunt.

Special Contents: The Shogun goes Oshishigari (Boar Hunting) at Koganehara in Shimousa Province

Farmer-beaters

In the shogunal deer hunts, it was the job of the farmer-beaters to drive prey into the hunting ground (the vicinity of present-day Matsuhidai). The hunt headed by Ienari, the 11th shogun, in 1795 involved the participation of more than 70,000 beaters from 381 villages. These farmers drove animals into the hunting ground from as far away as the province of Hitachi in the north, Otaki in the south, and Choshi in the east. Marching behind a banner on which were written the names of their province and village, and the number in their group, they carried bamboo sticks, bamboo whistles, and food, and used guns and fireworks in the beating work.

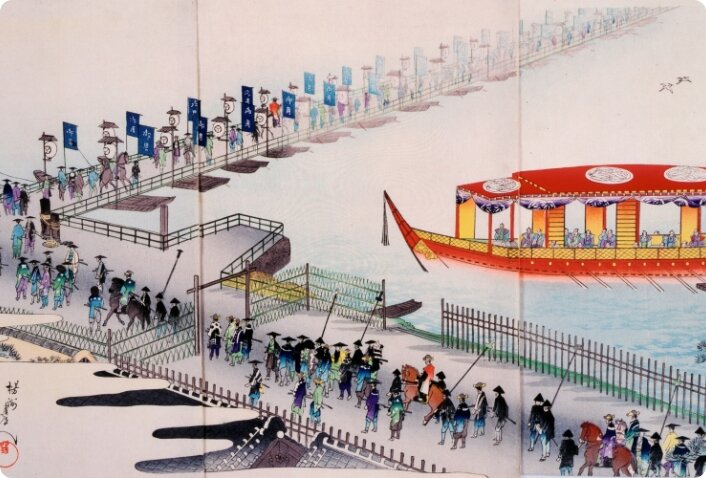

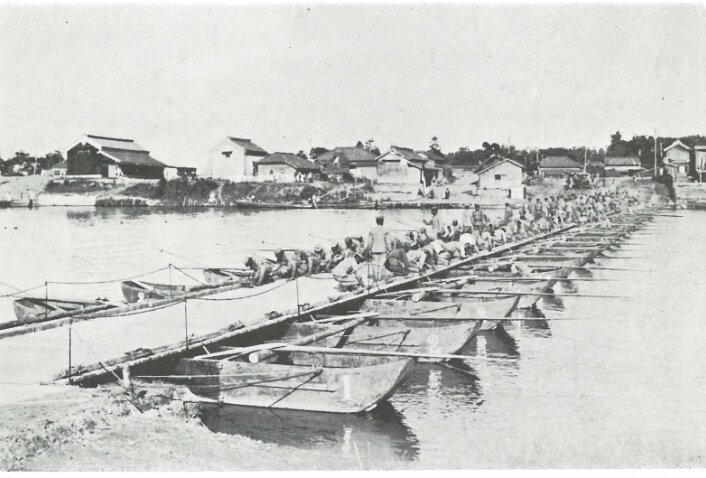

A floating bridge of boats on the Edo River

As a matter of official policy, the Tokugawa shogunate government did not have the Edogawa River bridged, but this did not apply to the shogun's hunting expeditions, when a temporary bridge of boats was constructed for the shogun to cross the river. This was done by lashing more than 20 boats together, putting planks across them, and filling the hulls with straw and earth up to the rails on top of their sides. Even handrails were attached to this floating bridge. The Kirinmaru, the shogun's vessel, was moored somewhat downstream of the bridge, in case of emargency.

After the long period of political maneuvering by the samurai class ended, Japan was transformed from an agriculture-based country into a modern country, i.e., a strong economic power that emphasized its manufacturing industry.

During the period from 1868 to 1945, Japan fought several wars and suffered many tragedies. On the other hand, that was also the period that Japanese people struggled to liberate themselves from poverty and superstition, through the new knowledge.

Daily life at Matsudo also reflected the atmosphere of the times.

-

View larger photo

View of Matsudo's ferry crossing from Kanamachi

Explanation Before the opening of the Joban Line Date Around 1908 Possessed by Katsushika City Museum -

View larger photo

A steam locomotive crossing a Joban Line railway bridge and a sailboat on the Edo River

Date 1910 Possessed by Susumu Oka -

View larger photo

The Naya riverfront at Matsudo, at the end of the Meiji Era

Date Around 1910 Possessed by Tojo Museum of History (photograph by Tokugawa Akitake) -

View larger photo

Treadmill used to move water from irrigation channels to rice paddies

Explanation Rice Paddies along the Edo River Date Around 1910 Possessed by Tojo Museum of History (photograph by Tokugawa Akitake) -

View larger photo

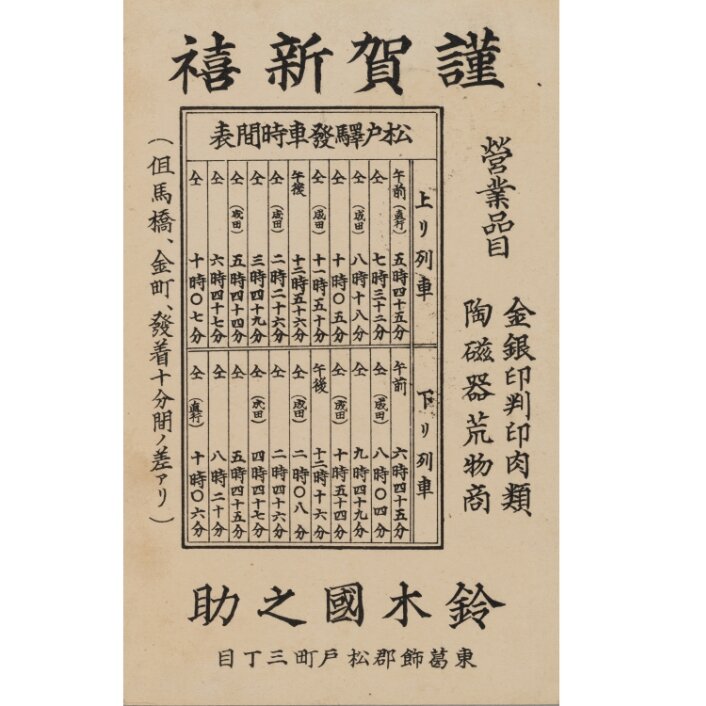

Matsudo Railway Station train timetable for 1911.

Date 1911 Possessed by Matsudo Museum -

View larger photo

Rickshaws at the Matsudo Railway Station

Date 1911 Possessed by Tojo Museum of Hisotry (photograph by Tokugawa Akitake) -

View larger photo

Higashi Katsushika-gun County Office in Chiba Prefecture

Explanation Matsudo-machi Date 1910 - 1920's Possessed by Previously owned by Makoto Yoshino and now in the possession of Nagareyama City Museum -

View larger photo

Transportation of fertilizer for shared use

Explanation Kogane-machi, Nakakanasugi Credit Corporative Date 1910 - 1920's Possessed by Previously owned by Makoto Yoshino and now in the possession of Nagareyama City Museum -

View larger photo

Matsudo-machi as viewed from across the river

Date 1910 - 1920's Possessed by Previously owned by Makoto Yoshino and now in the possession of Nagareyama City Museum -

View larger photo

Yagimura Fire-fighting Team in front of the Matsudo Police Station

Explanation Yagimura was located in the south of present-day Nagareyama City Date 1910 - 1920's Possessed by Previously owned by Makoto Yoshino and now in the possession of Nagareyama City Museum -

View larger photo

Matsudo-machi Town Office

Date 1910 - 1920's Possessed by Previously owned by Makoto Yoshino and now in the possession of Nagareyama City Museum -

View larger photo

Mabashi Railway Station

Date 1925 Possessed by Previously owned by Makoto Yoshino and now in the possession of Nagareyama City Museum -

View larger photo

Bridge-construction training of Japanese Army military engineering school students

Explanation Near the Naya riverfront of the Edo River Date 1926 Possessed by Katsushika City Museum -

View larger photo

Katsushika Wooden Bridge

Date Before 1927 Possessed by Previously owned by Makoto Yoshino and now in the possession of Nagareyama City Museum -

View larger photo

A "Watanabe" bus running through Matsudo-machi 2-chome

Explanation A section of the former Mito Highway near the Matsudo Railway Station Date Around 1930 Possessed by Unknown -

View larger photo

A scene in front of the Matsudo Railway Station on a typical day

Date Around 1930 Possessed by Unknown -

View larger photo

A "Hayashi" Bus running through the neighborhood of Akiyama

Explanation Matsudo - Akiyama Route Date Around 1932 Possessed by Unknown -

View larger photo

Visit of a prefectural governor to observe the Chiba Prefecture Joint Air-Defense Exercise

Explanation In front of Matsudo-machi Town Office Date 1939 Possessed by Unknown -

View larger photo

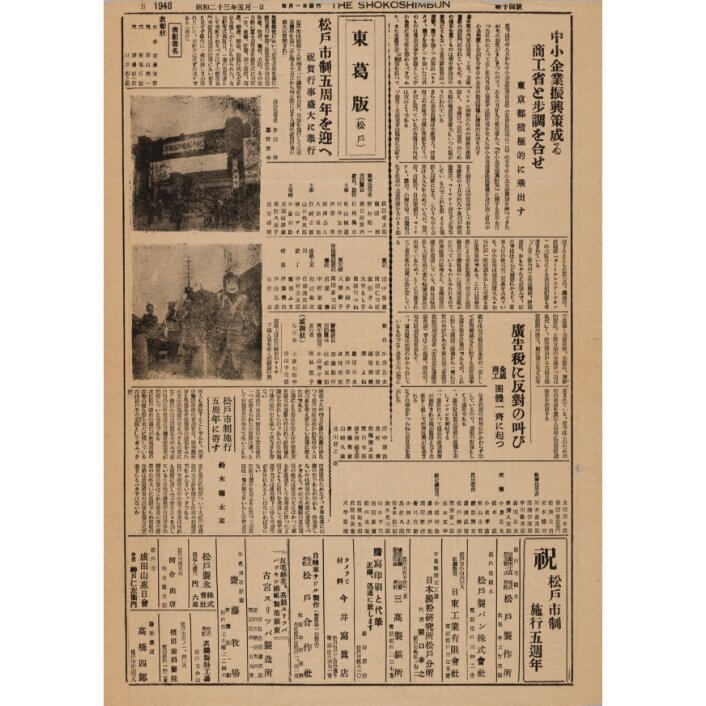

Newspaper reporting the 5th anniversary of the Matsudo city government

Explanation Issue No. 14 of the "Shoko" Newspaper Date 1948 Possessed by Matsudo Museum -

View larger photo

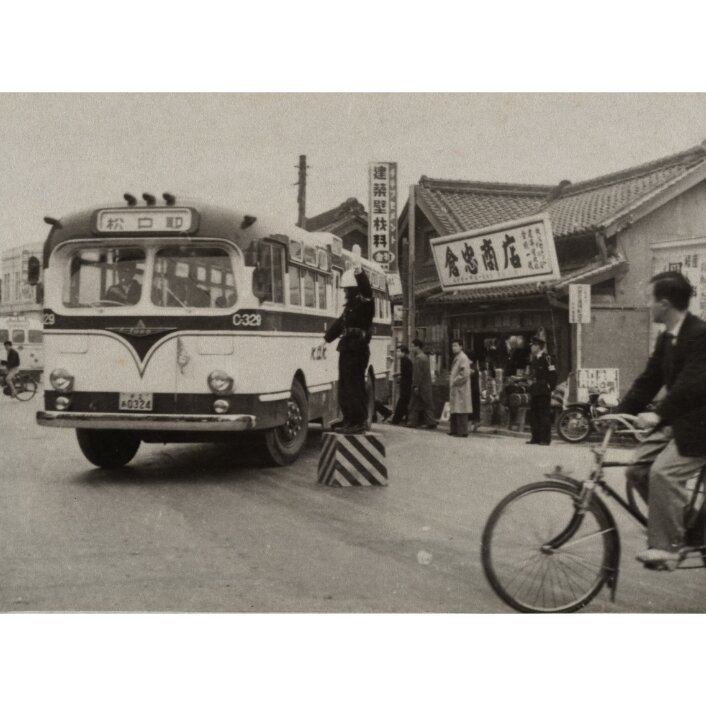

A policeman controlling traffic at Matsudo 1-chome, Matsudo City

Explanation At the intersection of Matsudo Ekimae Street and the former Mito Highway Date 1959 Possessed by Unknown

Shitaya, Yatsu, and Dai

The west side of Matsudo City is covered by lowlands along the Edo-gawa River, while the east side is connected to the vast Shimosa Plateau, giving each area its unique landscape. These areas are called Shitaya, Yatsu, and Dai because of their different geographical conditions, and until the rapid development of residential land, each had its distinctive lifestyle.

Shitaya

Shitaya is a term used to refer to the low-lying area in the western part of the city between the Edo-gawa River and the Shimosa Plateau at an elevation of 2 to 5 meters, where rice paddies spread all over the land. The Sakagawa River, which collects water coming down from the plateau and flows from north to south, often caused flood damage during the autumn typhoon season, so a stable harvest could not be expected.

Rice paddies in the Shitaya zone

Many early rice varieties were planted, rice planting was completed before the May festival, and harvesting was finished by mid-September. The harvested paddies were hung on alder trees planted between the paddy fields to dry. Treadwheels called Fumiguruma were used to lift water to the rice paddies.

Boats

In addition to the canals along the sides of the rice paddies, other canals called Hori run from north to south. In the past, boats about 4 or 5 meters long were used in the Holi to transport rice and other crops. Many houses hung the boats under the eaves of the main house or barn as a precaution against floods.

Dwellings in the Shitaya zone

The houses in this village are arranged in a straight line from north to south, and this is thought to be because the houses are located on a slightly elevated area of a natural levee. The entire premises are covered with Jingyo or earth fill, and in this house, the storehouse behind the main house has been raised even higher in preparation for flooding.

Yatsu

Yatsu is a term used to refer to a valley carved into the plateau, and in the city area, it refers to the dendritic valley found on the Shimousa plateau. The elevation of this village is 10 meters above sea level at the bottom of the valley and 30 meters above the table, making a specific elevation of 20 meters. The valley floor is covered with small paddy fields (Yatsuda), which are irregular in shape compared to the paddy fields in the Shitaya zone. The surrounding plateau was used for fields and forests called Yama.

Yatsuda

Yatsuda were rice paddies that mainly utilized cold spring water flowing from deep in the valley and were wet paddies with incomplete drainage. There were also muddy paddies soaked in water up to the waist in some spots, and to prevent their feet from being caught in the water, people wore snowshoe-like clogs called Kanjiki or placed bamboo and pinewood in the paddies to serve as footing.

Yama

Except for the fields, most of the plateau was covered with forests called Yama, which included cedar and pine forests in some areas, and thickets of Shii, Konara oak, sawtooth oak, and other trees provided fuel (branches) and manure (fallen leaves). Back ladders called Shoibashigo were used to transport fuel twigs on slopes that were too steep for carts to climb.

Dwellings in the Yatsu zone

The edge of the plateau facing south or east is often chosen for dwelling in this village. This house also backs up against the plateau to the west, protecting it from the northwesterly winter winds (monsoon), along with the tall zelkova and Shii trees surrounding the house and facing the east where it has a clear view.

Dai

Dai is a term used to refer to high ground and indicate the gently undulating land at an elevation of 25 to 30 meters above sea level on the Shimousa plateau that extends eastward from the city limits. The village has been developed in a strip of land, with each house having a field, a compound, and a forest called Yama connected to form a single parcel. In addition to planted pines and cedars, the Yama were covered with thickets of Konara oak, sawtooth oak, and other trees, and sawtooth oak was used to make charcoal.

Farm fields in the Dai zone

The largest acreage was winter wheat, with barley harvested at the end of May and wheat in June. Okabo (upland rice), sweet potatoes, and taros were produced in between the wheat crops. In addition, radishes, leeks, and burdocks were also grown, and backpacks were used to transport the harvested vegetables.

Wells

They dug either main wells about 7 to 12 meters deep or tray wells 2 to 6 meters deep. The main wells were dug down to the Narita Formation, a sandy layer below the Kanto Loam Formation. In contrast, the tray wells utilized groundwater accumulated in places in the Kanto Loam Formation. Since there are no rivers or springs in the area, well water was an essential water source for daily life.

Dwellings in the Dai zone

In this village, land use was regular, with every house having a forest called Yama on the north side behind the house and a field on the south side. This house is related to the development of the community, and the zelkova trees planted around the house show the landscape at the time of development.

Birth of the Tokiwadaira Housing Complex

The city of Matsudo was to undergo an immense transformation, from an area where agricultural made up the majority of land use to a residential city in the Greater Tokyo Metropolitan Area. One of the first steps in this transformation was the construction of the Tokiwadaira Housing Complex by the Japan Housing Corporation (JHC). Consisting of 4,839 units, the complex was large-scale collective housing, and opened for residency in 1960. This exhibit portrays the life of a household headed by a corporate office worker who commuted to Tokyo in 1962, in a unit equipped with all the latest conveniences.

Special Contents: VR of housing complexes in the Showa PeriodDanchi-zoku

Around 1958, the mass media began calling the residents of housing complexes danchi-zoku ("housing complex dwellers") and made much of them. In the "White Paper on National Life" released in 1960, danchi-zoku families were characterized as follows: "The head of the household is generally young. A fair number of the households consist of small, double-income families. Their income is high for their ages. Many spouses are intellectuals or white-collar workers employed at large first-rate companies or governmental/public agencies".

2DK

The term 2DK, which became synonymous with housing built by the JHC, refers to units with two Japanese-style rooms and a kitchen that doubles as a dining room (hence the DK). The design was based on the idea of having separate rooms for eating and sleeping. The units were also equipped with the latest facilities, such as flushing toilets and stainless steel sinks.

Stainless steel sinks

The sinks in housing built by JHC (the Japan Housing Corporation) were made of artificial stone when the JHC's housing complex project was first started. This was also the case for many residences built for the general populace. Over time, those sinks in JHC's housing were replaced with stainless steel sinks, as the use of stainless steel became popular in Japan. The JHC housing kitchen system, equipped with a stainless steel sink between a working space and a gas cooking stove unit, was called the "point system".

Black and white TVs

TV broadcasting started in 1953 in Japan. The price of the most popular 14-inch size black and white TV set was 175,000 yen. The price dropped to less than 100,000 yen in 1955, leading to the rapid spread of TV to general households. The TV set shown in this photo was purchased by a family living in the Tokiwadaira Housing Complex at the end of 1960.

Electric washing machines

The electric washing machine rapidly gained popularity during the period from 1955 to 1965. The residents of housing complexes built by JHC seemed particularly likely to obtain one sooner than the population in general, according to the "White Paper on National Life" released in 1960. The electric washing machine served to free people, especially women, from the hard work of washing clothes by hand using a washtub and a washboard. By the way, a hand-operated type roller-wringer was used to squeeze out water before the clothes were hung out to dry.

Electric refrigerators

Until 1960, the ice refrigerator - one that used ice to chill food - had been widely used. An electric refrigerator allowed people to make ice at home and preserve foodstuffs in it for a long time, making it possible for them to buy foodstuffs in quantity.

The makers of electric refrigerators vigorously advertised the point that if people bought an electric refrigerator they could drink cold beer at any time. The round door handle attached to the front door of this electric refrigerator could be used as a bottle opener.

Electric rice cookers

Toshiba Corporation started selling an electric rice cooker in 1960. The sales pitch was: "When the rice is cooked, the electric rice cooker will turn off automatically. You can scientifically cook rice that is rich in nutrition, without having to trust your intuition."

That is, the electric rice cooker allows people to cook rice successfully, without forcing them to take the trouble of controlling the fire in the kitchen cooking device.

Three years after the launch, Toshiba had shipped more than 2 million electric rice cooker units within Japan. Other electric appliance manufacturers followed in Toshiba's footsteps, and also started selling electric rice cookers, leading to their widespread use in households across the nation.

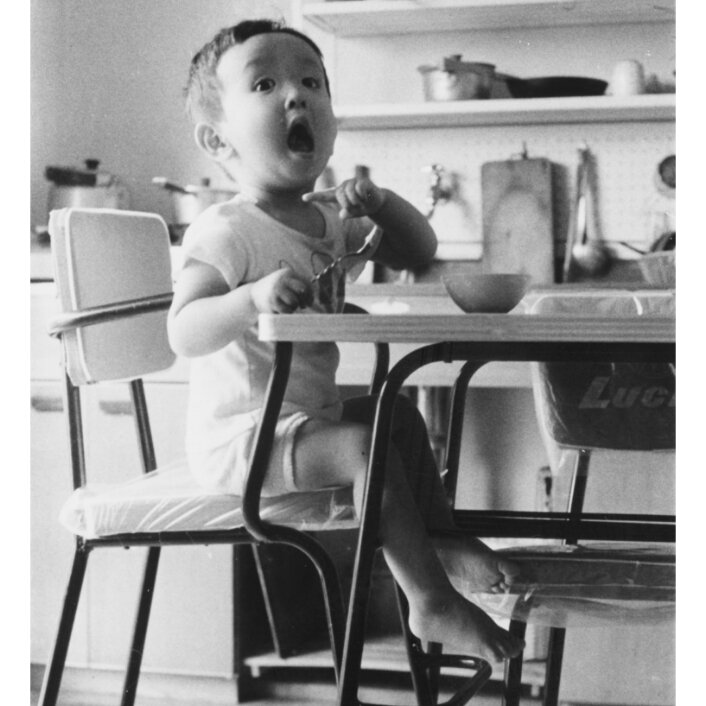

Dining table and chairs

When the Tokiwadaira Housing Complex was completed in 1960 and people started moving in, furniture dealers would sell dining table and chairs sets from open stands within the housing complex site. The family in the photo moved in the complex in 1960. They ate their meals at their chabudai table in the Japanese-style tatami mat room for a while after moving in. One year later, after their baby had gotten bigger, they bought a dining table set.

Flush toilets

Japanese people before 1960 were not yet familiar with Western-style toilets, including flush toilets. The handbook for residents prepared for the Tokiwadaira Housing Complex included a notice to prevent the drainpipe from being clogged up. It read: "Do not throw cotton, newspaper, or cigarette butts into the flush toilet." In addition, it also explained how to use the toilet, saying that the user should sit backwards.